Definitions

- GOT — Global Offset Table

- PLT — Procedure Linkage Table

- ELF — Executable and Linking Format

- DEP — Data Execution Prevention

- PHT — Program Header Table

- SHT — Section Header Table

Introduction

When I first learned to exploit computer systems — specifically Linux computer systems — a concept that always confused me was the purpose of the GOT and the PLT.

I knew that with a write-what-where vulnerability I could overwrite GOT entries to gain code execution. I also knew that it was some how linked to functions being called from external libraries, yet it took the writing of a binary patching framework for me to become fully acquainted with their purpose.

This post won’t directly discuss the GOT or PLT, neither shall it discuss their purpose. It instead details a fundamental principle of memory that must be understood to fully grasp their purpose.

If you find this post basic, boring or something else equally depressing, then just go on ahead and skip to the next post in the series.

R^X Principle

The R^X principles states that memory can be writeable or executable, never both. This prevents people and processes from accidentally or intentionally executing data. Therefore any area of memory that isn’t marked as executable — such as the stack — can never be interpreted as instructions and is limited as an attack vector.

Its a fairly easy concept to understand right, but why care? It turns out this inherit protection causes problems at run time as sometimes the code itself requires updating, primarily when loading shared libraries.

ELF Files

For those of you that don’t know anything about binaries, specifically those found on Linux. ELF is the format that governs how you take an arbitrary file, put it somewhere in memory and execute it like code.

At the end of the day every file, no matter how big or small, spectacular or pointless is just a sequence of numbers that are interpreted in a way that make them significant. You can talk about your clever binary, cybery-ninja artificial intelligence monitoring software to your hearts content. It does nothing but read numbers in order and that is that — well done, you’ve made something that is capable of reading a book.

ELF files are just the Linux equivalent of .exe files on Windows — their real name being portable executables or PE files. Linux also has shared objects files like Windows has .dll files, but remember they adhere to either an ELF or PE format. I’ve made this table to solidify my point.

- Linux Executable — .elf (ELF Executable)

- Linux Libraries — .so (ELF Shared Object)

- Windows Executable — .exe (PE Executable)

- Windows Library — .dll (PE Shared Object)

Note that “shared object” is synonymous with that of “software library”.

Format

So First things first — they have a format as is mentioned in the name, and this format has a specification. It’s really long and boring so I’m going to spare the details but if you’re a masochist or really need to understand its precise workings — Wikipedia is a good place to start.

With that being said, an ELF file contains the following four pieces of information.

- ELF Header

- Program Header Table

- Sections

- Section Header Table

All have a specific purpose but I’ve opted to spend most of my time within the realms of the PHT. It’s the most important piece of the puzzle and is seldom talked about.

Header

The header much like every other file contains information that describes itself such as its type, where it begins, its size and even what type of processor it can run on. It’s always at the beginning and lets our operating system loader know how to read the contents.

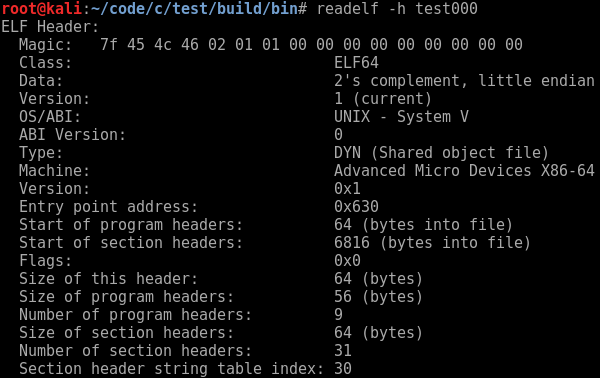

It also contains the entry point — this is the address of the first instruction that the processor will begin executing from once the file has been loaded into memory. You can use the command “readelf -h” to view its contents.

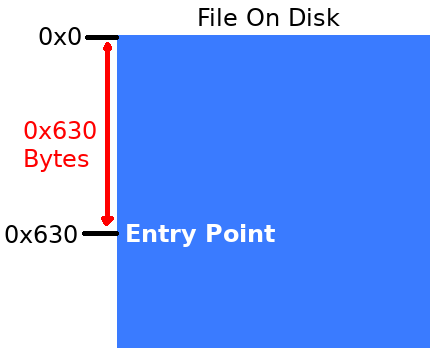

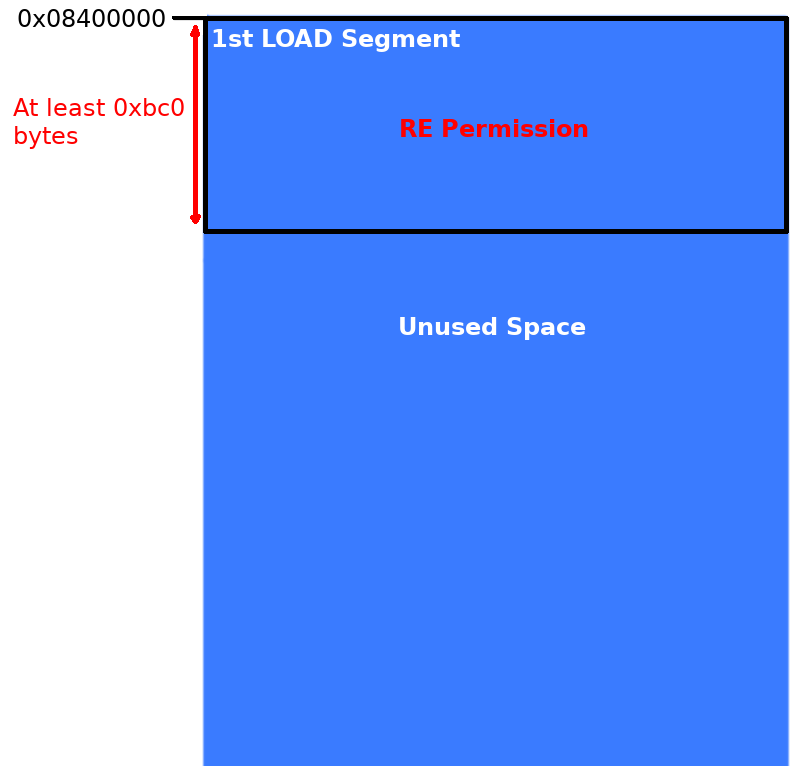

The entry point address for test000 is listed as an offset from a base. On disk this base is the beginning of the file and in memory it’s whatever address the operating system loaded the process at — the diagrams below visualise these concepts.

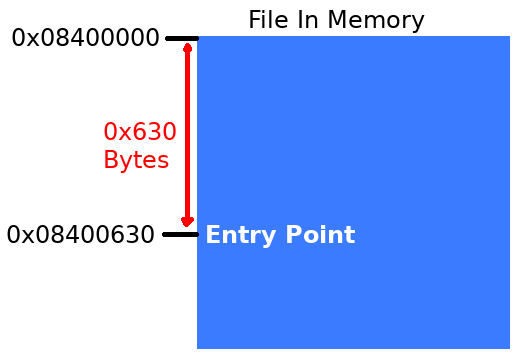

In the second instance the file has been loaded into memory and the entry point is at the same offset as it was before — this time with a base address of 0x08400000.

By now you’re probably wondering how the file was taken from disk and loaded into memory at a location that just happens to be correct. Well folks that’s the point of the PHT and SHT.

PHT

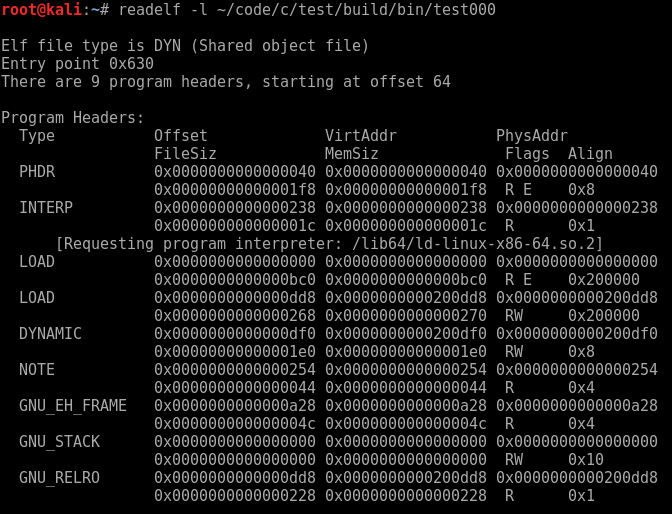

Let us begin by having a closer look at the PHT by issuing the command “readelf -l test000”. The image below shows a truncated version of this output.

You may also note that on your screen there’s a list of what sections are mapped to each segment — segments being contiguous blocks of memory described by a single PHT entry. Together they’re just a list of memory allocations the operating system should make when loading the process.

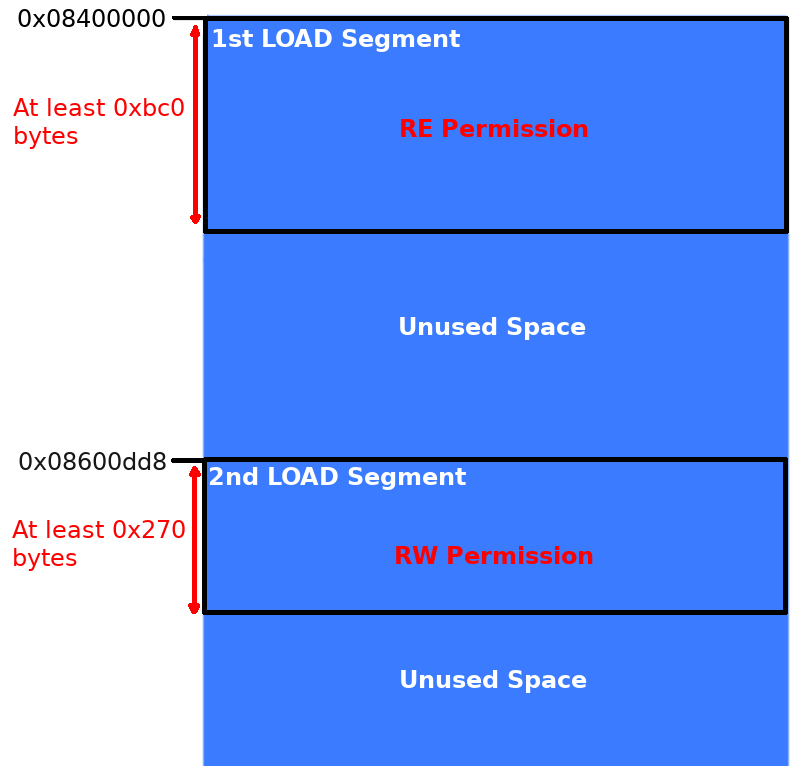

If you refer to the PHT dump above there are two segments marked as load types, the first has executable permission and the second has writeable permission.

The first one tells us that at the at the beginning of the offset — currently 0x0 — map some executable memory that’s at least 0xbc0 bytes large and aligned on a boundary of 0x200000. The second load entry asks for this to begin at 0x2000dd8, be made writeable and must be at least 0x270 bytes large.

Pragmatically the operating system loader must perform the following actions.

- Ask the operating system for adequate memory space and return the base address.

- The operating system gives us the base address 0x08400000.

- Ask the operating system to mark the first load segment as readable and executable.

- Ask the operating system to mark the second load segment as readable and writable.

- Repeat until all PHT entries have been mapped into virtual memory.

Sections and SHT

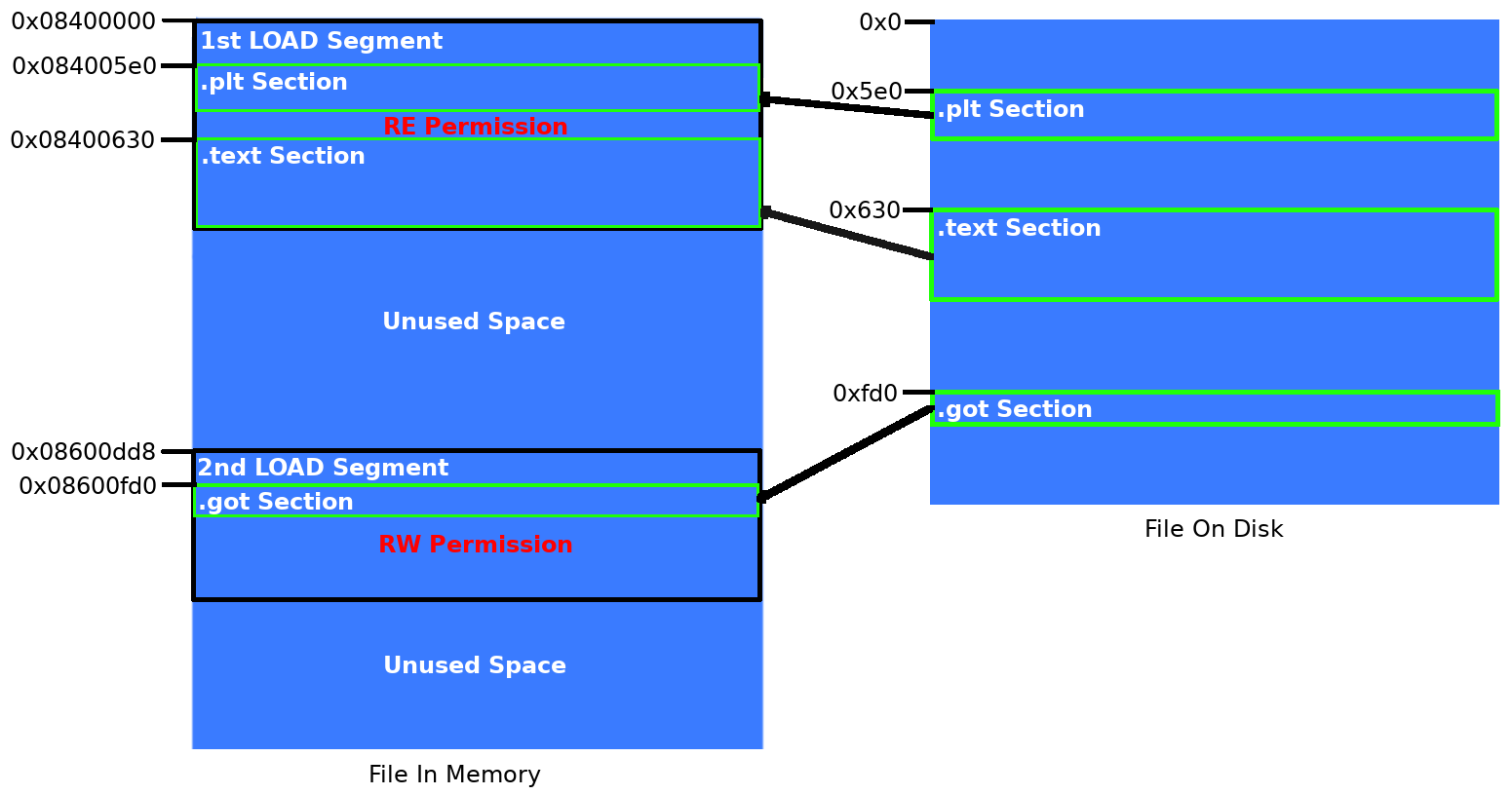

At this point we have a bunch of memory blocks — segments — ready to recieve the file contents. Now it’s up to the loader to do the rest by reading the SHT entries and placing their file sections at the appropriate addresses.

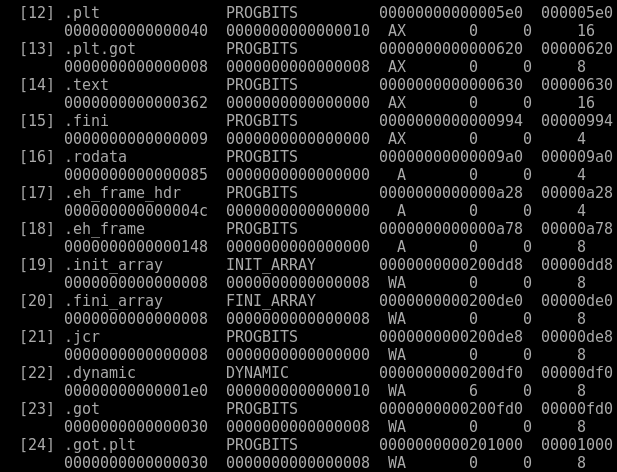

Depending on which segment a section is mapped into dictates whether or not it is read only, readable and writeable or readable and executable. We can view the section header table and its entries using the command “readelf -S test000”.

The SHT bears some familiarity to the PHT as it contains data such as address offsets, sizes and alignment information. Lets run through the next stage of the loading process by manually mapping these sections into their respective memory segments.

The most important take away is that sections containing code are copied into the readable and executable segment, where as sections containing non-read only data are copied into the readable and writeable segment. This means while the process is running we cannot write to the .text or .plt, but we can write to the .got.

Conclusion

As we’ve covered the basics of how ELF files are mapped into memory we can start looking at how we resolve libraries at load time. This is where the GOT and PLT come into their own — they help in the resolution of libraries without breaking the R^X principle.

If you have any additional questions or would like to organise a fight please hit me up on Twitter @JeffJerseyCow.